Besides Earth itself, Mars is the most-studied planet in the solar system. The 47 missions that have been launched since the start of the space age have put probes in orbit and landers on the surface from half a dozen space agencies. One reason, of course, is that Mars is relatively close. Another is that Mars appears to have had plenty of liquid water on its surface in the past. And where there is water, astrobiologists get excited about the possibility of life.

But Mars and Earth are not the only places in the solar system that either have, or have had, water. On October 13th, if all goes according to plan, a NASA probe called Europa Clipper will blast off from Florida. As its name suggests, the mission’s target is Europa, one of the biggest of Jupiter’s 95 known moons.

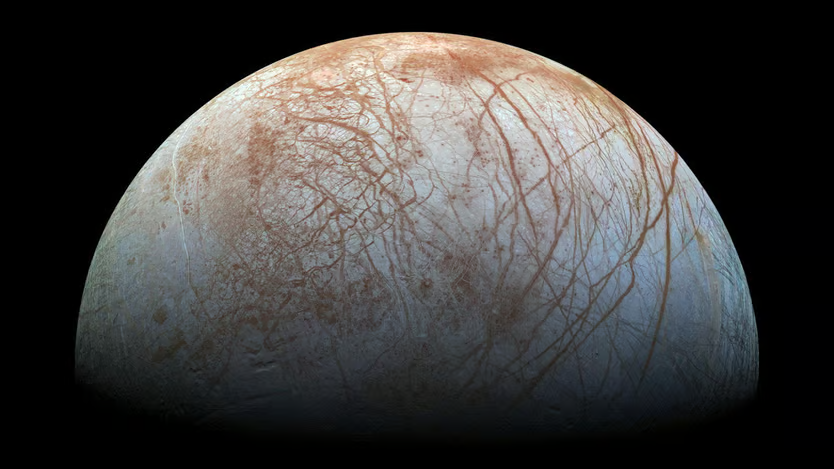

Europa is a snowball slightly smaller than Earth’s moon. It has an atmosphere that is thin to the point of non-existence, a crust of water ice and a surface temperature of around -180°C. But scientists think a vast ocean exists beneath the ice, kept liquid by friction produced as Europa is flexed and kneaded by Jupiter’s powerful gravity. Over the past few decades scientists have become steadily more excited about the life-bearing potential of such “icy moons.” Besides Europa, these also include Ganymede and Callisto, two other Jovian moons, Enceladus, which orbits Saturn, and Triton, the biggest satellite of Neptune.

Europa’s icy crust is thought to be tens of kilometres thick. Europa Clipper will therefore not be able to tell whether there actually are any aliens swimming around in the depths. Instead, its job is to assess whether the moon is the sort of place where life might plausibly arise. One of the probe’s tasks will be to characterise the size and saltiness of the ocean. NASA’s present best guess is that it is varies from 60km to 150km deep. If that is right, then, despite its small size, Europa would have about twice as much liquid water as Earth does.

But although water’s chemical properties are thought to be extremely useful (and possibly even vital) to the development of life, water by itself is not enough. To qualify as habitable, a world needs enough other elements to allow complex chemistry. Besides the hydrogen and oxygen in water, one common shortlist adds carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus and sulfur.

All of those elements have already been found on a different icy moon—Enceladus. Plumes of that moon’s ocean water jet out into space through cracks in the crust. In 2008 Cassini, a European spacecraft, flew straight through one of those plumes. That revealed that Enceladus possesses all six of the elements on the astrobiological list, some of which are locked up in relatively big, complicated molecules.

Whether such plumes exist on Europa is an open question, says Robert Pappalardo, Europa Clipper’s chief scientist. Europa’s ice shell is much thicker than Enceladus’s, he says, which makes it less likely that cracks or fissures in the surface would reach all the way to the ocean beneath. Some tantalising—but uncertain—images from telescopes nevertheless show things that look plume-like. But follow-up observations with the space-going James Webb Space Telescope have so far failed to spot any.

If plumes do not exist, then Europa Clipper will have to content itself with examining the moon’s surface. That surface is notably smooth and relatively free from impact craters, which suggests it is regularly renewed by processes a bit like plate tectonics on Earth. That, in turn, suggests that chemicals that form on Europa’s surface—from impacts, or as dust from Jupiter’s rings, and modified by Jupiter’s radiation—might have a way down to the ocean. Studying Europa’s surface may therefore give valuable clues as to what lies beneath.

The final ingredient for a habitable world is a source of energy for life to exploit. Whatever that might be on Europa—far from the sun, and entombed below kilometres of ice—it will not be sunlight. If anything does live in the depths, it might adopt a similar strategy to the organisms that live around the hydrothermal vents that dot the floor of Earth’s oceans. These vents are cracks in the ocean floor that spew chemical-rich water into the seas above.

Almost every living thing on Earth ultimately depends on photosynthesis for its energy. But the ecosystems that surround the vents are an exception. The “chemosynthetic” bacteria that sit at the bottom of the food chain exploit chemicals bubbling up from the vents—in particular hydrogen sulphide—to obtain energy. The discovery of such non-photosynthesising ecosystems in the 1980s was one of the things that got scientists excited about the possibility of life on icy moons in the first place. Analysing Europa’s surface chemistry may give clues as to whether something similar could, at least in principle, be happening hundreds of kilometres down on the moon’s ocean floor.

And Europa Clipper will not be the only icy-moon explorer at Jupiter. Last year saw the launch of a European probe called the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE). It will likewise examine Europa, as well as Callisto and Ganymede, two other moons that are also thought to have oceans. The vagaries of orbital mechanics mean that, despite its later departure, Europa Clipper will arrive in 2030, a year before JUICE.

You may attempt a landing there

If the findings from the two missions are sufficiently exciting, then the next step could be to send a lander. Scouting for landing sites on Europa is another of Europa Clipper’s goals. But the probe will not be able to build a perfect map of the moon’s surface. Jupiter’s powerful magnetic field produces areas of intense radiation near the planet, enough to fry any spacecraft that lingers in Europan orbit too long. Instead Europa Clipper will make 49 looping flybys, gathering as much data as possible each time before retreating out of the worst of the radiation.

Worries about radiation nearly led to Europa Clipper missing its launch window entirely. Earlier this year it emerged that some transistors—tiny electronic switches—that were supposed to be hardened against radiation were not in fact as hardened as had been hoped. After months of frenetic analysis, the probe’s builders are now reasonably confident that they can work around the problem. The world’s alien-hunters will be hoping they are right.